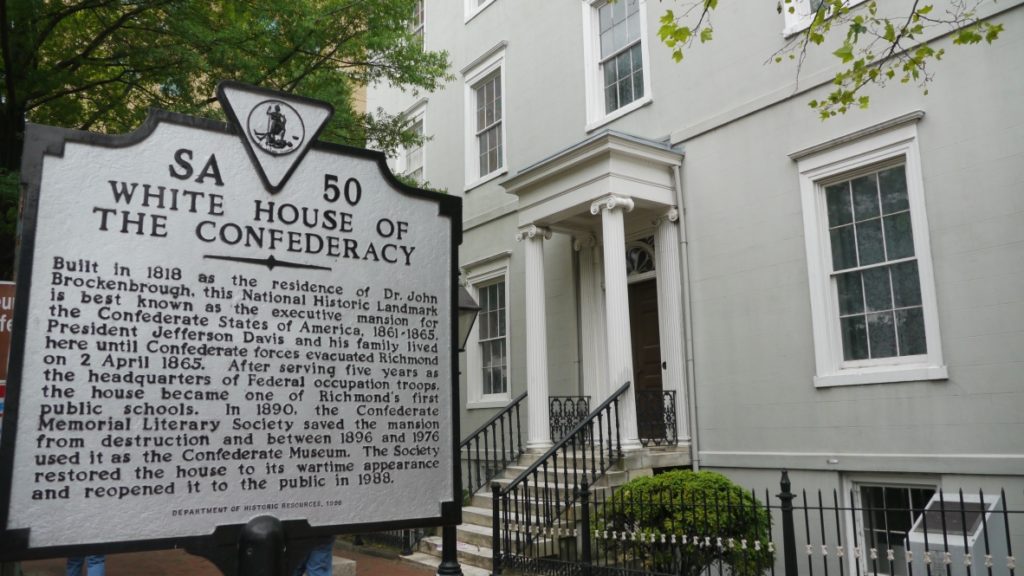

In Richmond, Virginia, this week, a monumental statue of Jefferson Davis was toppled from its perch by a popular uprising. In observance of that, I am proud to publish a section of Here Lies America that has never been seen before: my visit to the White House of the Confederacy. This segment was trimmed for space from the final manuscript just before publication.

The White House of the Confederacy

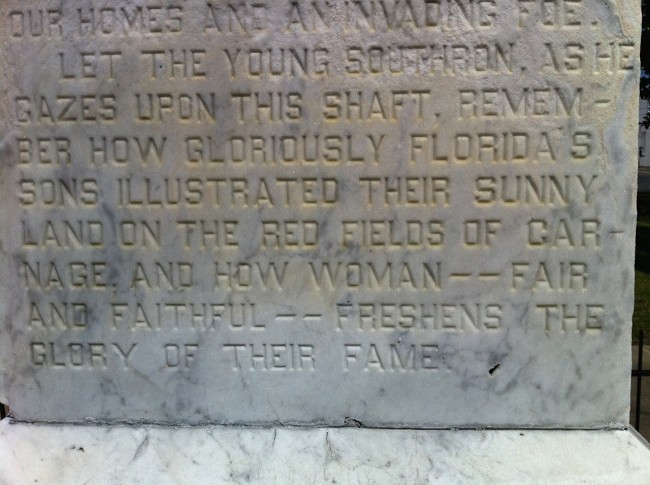

Just going by evidence, you could say the Lost Cause women’s groups were fanatics. In addition to slapping up thousands of Confederate memorials nationwide, they never stopped hoarding relics. Dutiful members emptied their attics and hope chests of anything related to the Civil War, and in time, their mania had bequeathed researchers with an unparalleled catalog of papers, artifacts, portraits, flags, busts, photographs, and bizarre bric-a-brac.

All of that stuff had to go somewhere, and given the mistrustful character of the neo-Confederate movement, that place was not going to be the Library of Congress. So in Richmond, the former seat of the Confederacy, the Ladies Hollywood Memorial Association (one of the first Civil War women’s groups) saved the former Confederate White House from demolition for the sweetheart price of $1 and turned it into The Confederate Museum.

My visit to the Richmond’s Museum of the Confederacy a few years ago, just before it was renamed as the American Civil War Museum, indicated that now that time has put distance between us and those early fanatics, the modern expression of “Southern Truth” has diversified. Or at the very least, it learned how to trade overt condescension for wording that has the power to seed doubt. One sign at the MoC (“Why Secession? Why War?”) puts the cataclysm down to a “disagreement over Constitutional principle.” It even mentions slave or slavery four times. From the 1890s through the 1930s, the United Daughters of the Confederacy would almost never have put those dirty words on a public tablet, preferring religiously tinged terms like honor and duty as the usual surrogates for human bondage.

The “Rosette” display

The Museum of the Confederacy now adjoins the preserved Confederate White House, but there’s still the heavy perfume of sacrificial romance in the way history is expressed, particularly in a near-Catholic obsession with relics. See the handkerchief that bound Stonewall Jackson’s wounds—it was once blood-soaked, but now it just looks vaguely dirty. There’s a cracked plate that one Emily H. Booton of Luray, Virginia, allegedly used to knock out a Union pillager who tried to eat her butter and rolls; it’s cradled against the wall to better display the hairline fissure borne of resistance. There was also a bullet “rosette,” squashed like a leaden flower, that was formed when a Rebel bullet melded with a Yankee bullet mid-flight in Spotsylvania. It’s a lyrical symbol for a clash of brotherhood but a bathetic way to interpret mutual execution—you’ll find similar collided bullets on display everywhere from Petersburg to Gallipoli, as if the metaphor of intertwined bullets could ever speak louder than the millions of others that found their true marks.

You can still see the sleeveless coat Jefferson Davis wore when he was captured in Georgia in May, 1865. It’s mounted alongside a broadside declaring that the garment disproves once and for all the humiliating rumor that Jefferson Davis was arrested wearing women’s clothing. To the outsider, it seems like a strange thing to get defensive about Davis’ sartorial choices during his surrender, but not in the land of Friday Night Lights. Assertions of masculinity are a foundation of the Southern self-image, and rarely will you find a hero in the pantheon of Southern lore whose manliness has been openly compromised.

You can still see the sleeveless coat Jefferson Davis wore when he was captured in Georgia in May, 1865. It’s mounted alongside a broadside declaring that the garment disproves once and for all the humiliating rumor that Jefferson Davis was arrested wearing women’s clothing. To the outsider, it seems like a strange thing to get defensive about Davis’ sartorial choices during his surrender, but not in the land of Friday Night Lights. Assertions of masculinity are a foundation of the Southern self-image, and rarely will you find a hero in the pantheon of Southern lore whose manliness has been openly compromised.

There was also, need you have asked, the requisite lock of Robert E. Lee’s hair. To Confederate shrines in the South, a lock of Lee’s hair is what IMAX movies are to science museums — any self-respecting institution has to possess one. If Nathan Bedford Forrest had farted in a jar, I have no doubt the MOC would have treasured that, too.

Visitors may sign up for a tour of the White House of the Confederacy next door. This building was, in no minor way, the seat of slavery, where the ultimate triumph of bondage was planned.

Today the White House of the Confederacy is dressed as a nineteenth-century mansion even though it has lived several lives since then, including as a museum and a schoolhouse. About 25 of us (all white, most older than 50) on this sold-out tour were confined to a waiting room near the back door until the appointed time. Finally, a door on the far wall opened, and our guide appeared.

A woman behind me began to gasp, but quickly converted it into a discreet throat clearing.

Our guide to the seat of the Confederacy was an African-American.

His name was Abdur Ali-Haymes, he told us with an intoxicatingly seductive Southern accent. He told us that guiding here, at what he always simply called “the White House” was his first civilian job after a lifetime spent as an operations manager in the U.S. Army (later, I learned, he had risen to the non-commissioned rank of Sergeant major and was much admired by the United Daughters of the Confederacy for it).

Ali-Haymes’ charisma and obvious guiding talent appeared to come from his delight in the subversion of identity, starting with his effortless power to confound our racial expectations with his mere presence. He could barely contain clandestine glee at repeatedly challenging our expectations about the Confederacy. His interpretation could be said to border on performance art because its central objective was to repeatedly revel in the overturning of assumptions.

With 200 tours a year under his belt, he also knew how to keep the surprises coming. “No tweetering. No setting on my furniture. No touching my wallpaper. No cameras. You can keep ‘em, but don’t flash ‘em in my house.” After taking time to thank those of us who had served in the military, he began the walking tour. “Let those ladies stand in front. General Lee wouldn’t want it any other way.”

It was hard to tell if Ali-Haymes was trying to modernize the Lost Cause or simply filling in the historical record — or if the two are even in conflict. “Jefferson Davis was one of the greatest Americans to walk America,” he announced with relish. “Unfortunately, history has not treated him fairly. If you had been living in the 1840s and 1850s, we would have known everything about Mr. Jefferson Davis, and absolutely nothing about Mr. Lincoln. And now things have reversed. Mr. Davis was such a great American who contributed a lot to this country.”

Davis rejected this anti-slavery design

For one, we were told, Davis placed the statue of Freedom at the apex of dome of the U.S. Capitol. “Had it not been for Mr. Jefferson Davis, who designed her to be placed there, she would not be there.” Ali-Haymes omitted the much nastier backstory: Davis, who in the 1850s was the U.S. Secretary of War, had refused to permit the installation of an earlier design for a statue that wore the traditional Liberty cap. A Phrygian hat represented manumission from slavery, and Davis said, essentially, that proud people who were not born slaves should never have to look at a statue like that. So, at once disregarding slaves and rattling his sword, Davis wouldn’t approve the figure atop the Capitol unless it wore a military helmet instead. A principal fabricator of the final statue was in fact a slave, Philip Reid, who wound up being freed while it was still being made. The antagonistic figure that crests the U.S. Capitol dome was installed in 1863, in the heat of war and five months after the South’s hopes of seizing Washington were smashed at Gettysburg. Because of that timing, the statue atop the Capitol wound up being a potent symbol of the rage of the Confederacy’s defeat, an accidental first member of the Lost Cause women’s groups. None of that information was in the tour.

Ali-Haymes followed that with an impressive roster of Jefferson Davis contributions that were made in the pre-war era, when Southern influence had a white-knuckle hold on national politics: Davis designed the two wings containing the House and the Senate. He came up with the idea for the Smithsonian. He designed the drinking water aqueduct used by Washington. He also gave Samuel Colt a government contract for his struggling revolver. (Ali-Haymes also did not mention what his contemporary, Sam Houston, thought of Davis. He called him “as ambitious as Lucifer and cold as a lizard.”)

Inside the Confederate White House (Carol M. Highsmith / Public domain)

Still, for shock, Ali-Haymes was a guide after my own heart. He used every slice of information to link his guy to the greater legend of America. For example, he made a point of mentioning that Davis’ war council, which met in this house in April 1862, included a grandson of Thomas Jefferson and a nephew of Patrick Henry—a nifty truth that simultaneously lends a pedigree to the rebellion and reminds you that the leaders of the Confederate movement were well-connected and elite. They were convinced they were classicists, and the direct inheritors of the next chapter of the heroic American tale. We were also carefully reminded reminded us that as the war wrapped up, it was the Confederates, and not the Union, that set their capitol Richmond ablaze to keep its resources from being used, even though the Federals usually take the blame. The North often gets erroneously blamed for the destruction of Southern cities, including Atlanta and Columbia, that the Confederacy actually had a hand in destroying. I was grateful that such shades of grey were part of the retelling.

Yes, Davis was a slave owner, admitted Ali-Haymes, but “a different kind of slave owner.” He never used the whip, he assigned black men to be his business managers, and when they were set free, he insisted they come up with their own last names instead of taking his own. To me, this set a pretty low bar for generosity. If you’ve spent years owning another man and forcing him to toil for your personal gain, don’t expect a party just because he’s finally permitted to select his own name.

As we arranged ourselves in the next room, I asked a tiny elderly woman if she’d like to stand in front of me to see better. Ali-Haymes halted the tour.

“What a gentleman!” he announced to the group. “You let the lady in! Where are you from, sir?” Everyone turned away from Jefferson Davis’ cigar case and stared at me.

“I’m from Atlanta originally,” I said. (Something in his sharpened tone told me I’d better try to fit in. I was about to be made an example of something.)

Ali-Haymes puffed up. “Southern gentility!” he bellowed, pleased that my behavior had sustained his favorite stereotype. “You let the ladies be in front. Always the ladies in front. We Southerners, we pride ourselves in chivalry.” Knowing chuckles all around.

“I see the gentleman here taking notes,” he finally informed the group about me.

Ah, there it was.

“He might be a news reporter, I don’t know.” He grinned at me until the pause became awkward.

I said nothing. I only smiled. He turned back to his tour, but by now I was tainted. Everyone else kept a wary eye on me as a member of the fake media. Now I felt like the very reason he thought we need Southern gentility. There I was, wanting to record information about history. Such a thing is suspicious in some circles.

Both Davis and Lincoln (whom Ali-Haymes unfailingly called “Mr. Lincoln,” not “President”), were structure-averse parents who liked to let their kids rampage wild throughout their respective executive mansions, but unlike Lincoln, Davis paid a price for it. He let them eat whatever they wanted, go to bed when they wanted, and get up at their leisure. He even gave his young son a miniature cannon cast nearby at Tredegar Iron Works, complete with gunpowder, to mow down toy Yankees—now it’s the only toy remaining in the Confederate White House that actually belonged to the Davis kids.

Joseph Evan Davis

Such lack of discipline cost the family dearly. In April of 1864, Davis’ five-year-old son, Joseph Evan, “was left unsupervised, went down the stairs to the east portico,” explained Ali-Haymes. “At that time, it was a two-and-a-half story drop, and he fell headfirst to the courtyard below.” He died an hour later. Several women in our group moaned disapprovingly. In a few years, another of Davis’ surviving sons was yanked out of Virginia Military Institute for sins unrecorded—or more likely erased. “To this day, Jeff Junior has the record for demerits at VMI,” said Ali-Haymes. (“It goes back to his child rearing!” scolded a man in the group, eager to locate an enemy to blame.)

As we left the Confederate White House, Ali-Haymes saw us out the door and once again thanked each veteran for their service to the military—the same federal military that he himself had faithfully served but Davis had spilled rivers of blood to crush.

This post was adapted from material collected for my book Here Lies America, which is about how the United States has memorialized its past tragedies at tourist attractions. (You can buy Here Lies America here.)

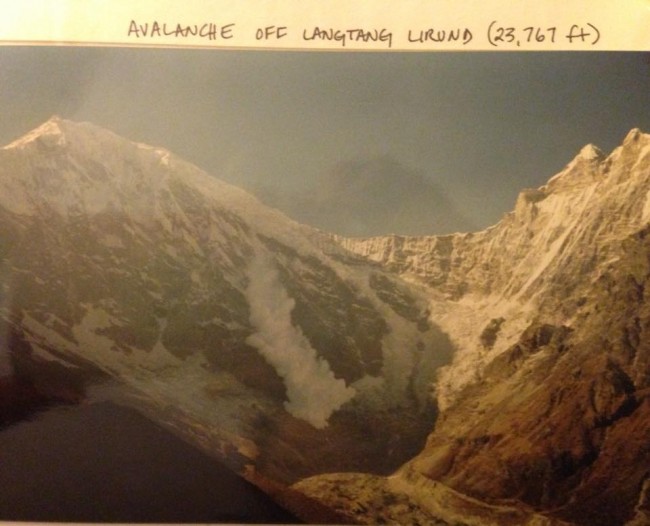

The Earth is an angry place, really. So much of it is roiling with overpowering and terrifying unconquerability. It’s a wonder humans have survived at all. The eastern seaboard of the United States gives you such a paltry idea of how formidably wracked the rest of the planet can be. So much of it is indescribable through words or lenses; its power lies in the ability to dash your life against mighty forces, or to move your soul by means of its nearly celestial gravity.

The Earth is an angry place, really. So much of it is roiling with overpowering and terrifying unconquerability. It’s a wonder humans have survived at all. The eastern seaboard of the United States gives you such a paltry idea of how formidably wracked the rest of the planet can be. So much of it is indescribable through words or lenses; its power lies in the ability to dash your life against mighty forces, or to move your soul by means of its nearly celestial gravity. … I did my laundry in a metal bowl with water fed by a plastic pipe from a mountain stream. I squatted over an aluminum bowl and shaved using a hand mirror in my wooden shack. You can see sky through the cracks between boards. Stoves belch smoke. You crap in a hole the size of a business letter framed by old wood. The sun is sharp and so is the wind. Your tea comes in tin cups. Iodine in your drinking water.

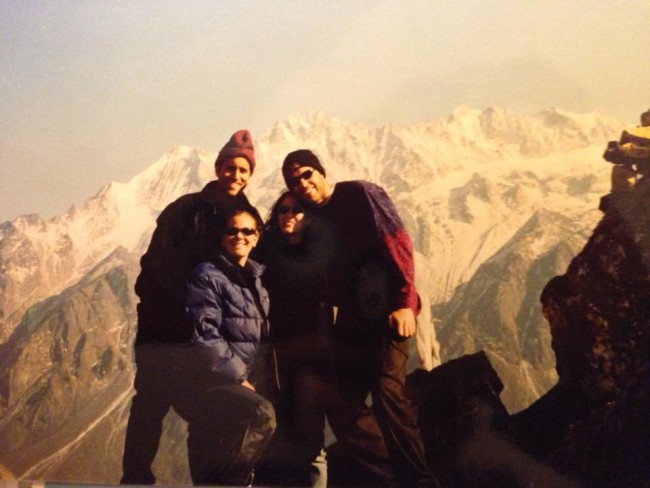

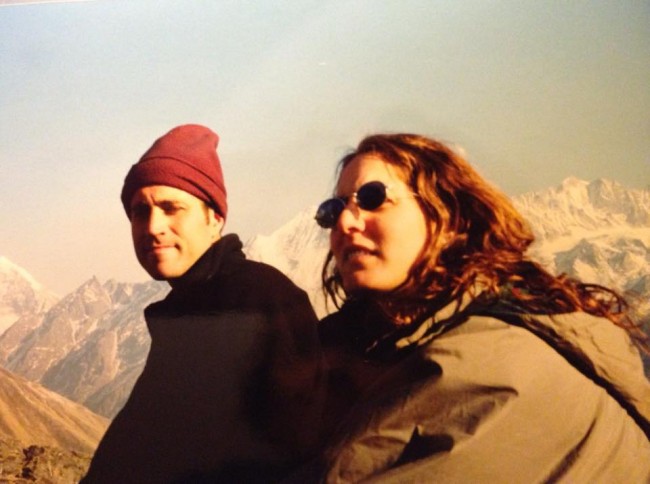

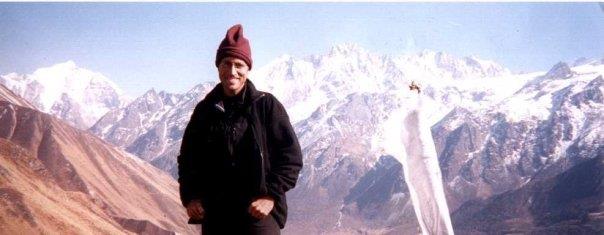

… I did my laundry in a metal bowl with water fed by a plastic pipe from a mountain stream. I squatted over an aluminum bowl and shaved using a hand mirror in my wooden shack. You can see sky through the cracks between boards. Stoves belch smoke. You crap in a hole the size of a business letter framed by old wood. The sun is sharp and so is the wind. Your tea comes in tin cups. Iodine in your drinking water. … Ian and Cathy suggested we climb the mountain looming over the village. For almost two hours, every step went up. At 4000m, air becomes less meaningful to your lungs. You have to slog. And slog, and look up to check your progress pitifully, and trudge, and cry to heaven, and after a long, long time of this you realize you’ve hit a sort of zen state—thereby erasing two important hours of your life—and you’ve summited.

… Ian and Cathy suggested we climb the mountain looming over the village. For almost two hours, every step went up. At 4000m, air becomes less meaningful to your lungs. You have to slog. And slog, and look up to check your progress pitifully, and trudge, and cry to heaven, and after a long, long time of this you realize you’ve hit a sort of zen state—thereby erasing two important hours of your life—and you’ve summited.