The sculptor Hendrik Andersen: “During one of Henry James’ visits to my studio [in Rome], he noticed a terracotta bust which greatly attracted him. It represented a boy of about twelve, not handsome, but with a look of eager intelligence and underlying melancholy which appealed to him. It was the bust of the young Count Alberto Bevilacqua, a boy of remarkable intelligence and character who used to spend every Saturday—his weekly holiday from school—in my studio, making little boats or reading to me while I worked. I was very strongly drawn to him and, in spite of the difference in our ages, a great attachment sprang up between us. Berto had lost his father and I felt he needed care and guidance. I used to take him with me to the many churches and picture-galleries in Rome and interest him in the great masterpieces of art, noting with delight how quickly he learned to appreciate their beauty and detect the weakness of inferior artists.

Being deeply attached to the boy and understanding him so well, it was a great pleasure to me to model a bust of him and, in Henry James’ opinion, I succeeded in conveying a vivid impression of the ager, enquiring mind and ardent spirit.

Not only did Henry James admire this work, however, but he offered to purchase it at a sum [US$250 in 1899] that enabled me to carry out plans for other work I had in my mind. I shall never forget how grateful I felt for his kindness in buying this little terracotta bust. I was delighted to think that the first purchaser of my work should be a man of such taste and discrimination and at the same time one whose good opinion I valued for personal reasons.”

The young Count Alberto Bevilacqua, a muse of sculptor Hendrik Christian Andersen, the special friend of writer Henry James. The bust remains in the home of Henry James, Lamb House, in Rye, England.

•

Henry James to Henrik Andersen, three years later, upon the death of Andersen’s brother: “The sense that I can’t help you, see you, talk to you, touch you, hold you close & long, or do anything to make you rest on my, & feel my deep participation – this torments me, dearest boy, makes my ache for you, & for myself; makes me gnash my teeth & groan at the bitterness of things. . . . This is the one thought that relieves me about you a little – & I wish you might fix your eyes on it for the idea, just, of the possibility. I am in town for a few weeks, but return to Rye April 1st, & sooner or later to have you there & do for you, to put my arm round you & make you lean on me as on a brother & a lover, & keep you on & on, slowly comforted or at least relieved of the bitterness of pain – this I try to imagine as thinkable, attainable, not wholly out of the question.”

Hendrik Christian Andersen and Henry James

•

The legendarily good-looking poet Rupert Brooke was a guest at Lamb House and a beneficiary of James’ mentorship. He never married. His portrait now hangs in the hall.

Rupert Brooke’s breathtaking beauty would never age. He died at age 27 of an infected mosquito bite.

•

Burgess Noakes came to Lamb House as a houseboy in 1902. Soon, he was Henry James’ personal valet, and during the Great War, he was recalled from service so he could nurse James in his final days.

Burgess Noakes was first Henry James’ houseboy, then his valet and butler, and finally his deathbed nurse.

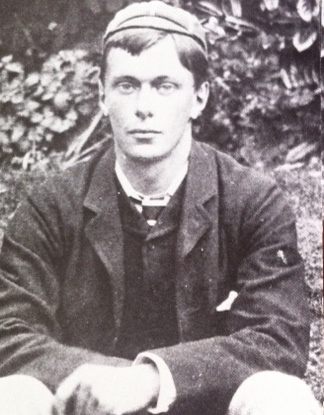

The writer E. F. Benson, the son of the Archbishop of Canterbury, first visited Henry James at Lamb House in July 1900 when he looked like this:

E. F Benson followed in James’ footsteps to the end

After James’ death, “Fred” Benson moved into Lamb House himself and became the second prolific writer to make it his working home. He even became mayor of Rye while living in his mentor’s former home. Benson also never married, but one of his special friends, pianist John Ellingham Brooks, moved to Capri after the Wilde trial and never came back.

I couldn’t help but notice all these images of young handsome men around Lamb House. The National Trust docent guide said that Henry James kept to himself, that there wasn’t much proof of anything, that there were reports of people coming to visit him and he’d just sit there quietly without saying much.

I think that’s hogwash. This is clearly a case of a legacy being passed down between men who only had each other for mentorship and support.

I have been reading Colm Toibin’s novel The Master about Henry James. The book takes a view about James’ instinct for privacy and the effect the Wilde trial had. The power of James’ writing lies in the unspoken undercurrents in relationships, and what you post here is fascinating. I presume you are quoting from a letter written by HJ?